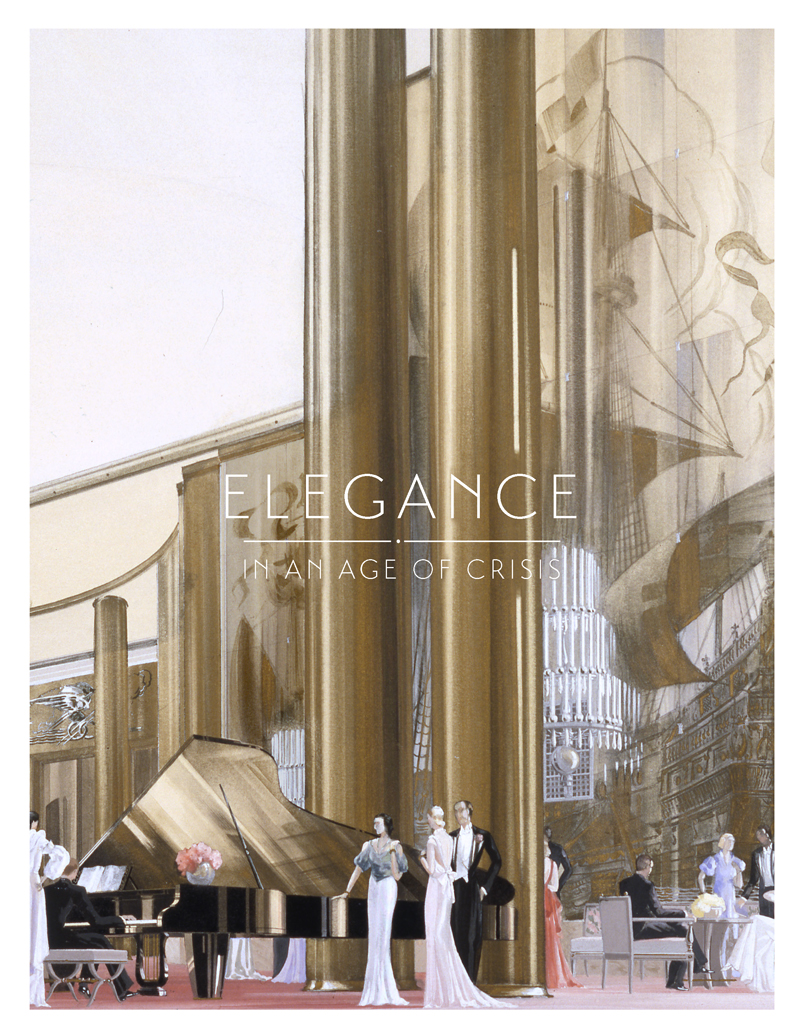

When I was a little girl I collected Moddess advertisements. I was too young to understand what Moddess was, really too young to even read, but every month I turned eagerly to the back cover of Ladies’ Home Journal where a full page color ad showed me a world far away from my suburban neighborhood. No one I knew had gowns like the ones I saw there. No one lived in rooms like the ones I saw in the ads. I stared at these pictures for hours and dreamed.

I had never heard of Charles James. He was not a household word in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Many years later I learned that Charles James was behind the 1948 ad campaign that launched my dreams. For it was James who persuaded Cecil Beaton to photograph five gowns so “any woman at a difficult moment can imagine herself a duchess.”

Charles James: Beyond Fashion took me into the world of the designer who launched those ads. Charles James’ goal was to “help women discover figures they didn’t know they had,” to make them fit of his dreams of perfection. Curators Jan Glier Reeder and Harold Koda of the Costume Institute have presented much more than a show of beautiful clothes. They have sought to analyze the architecture of James’ garments so we can gain an insight into the mind that created garments unique in the history of fashion. To a large extent, they have succeeded.

The exhibit is divided into two parts in two different galleries on different wings of the museum. James’ earlier work is shown in the lower level of the north wing. This is location of the new Anna Wintour Costume Center, which is the home of the Costume Institute. Of special interest is the small, overcrowded room, which shows James’ archive because it is here the curators, begin to wrestle with how James developed as a designer.

The walls are lined with James’ sketches. Here too are pictures and an album from an English childhood in the privileged upper classes of England, including life at Harrow where he met Cecil Beaton. After time in Paris studying art, James eventually went to Chicago where he opened a millinery shop in 1926. This experience was surely key in developing his sculptural technique. A milliner has to think in the round, knowing that all angles will be visible on the head. How he learned this craft is mysterious. James claimed he worked right on the heads of his clients, but that is unlikely unless he was draping a turban style. It is more likely that James blocked the hats to the proper size and then adjusted the fit and brim on the client. Three of his hats are on display. All show the asymmetric lines he would become known for.

Next to the hats are two small bolero jackets, whose label informs us that James shaped the collars using millinery techniques, steaming, pulling, and shaping the material so it curled around the neck at just the right angle. There are also dress forms, including the “Jennie,” a flexible form the designer developed so he could adjust it for different postures. A video from the time shows James constructing it.

Further along the same platform is a tiny blue baby jacket made for his son with an unusual armhole shaped like a flattened oval. Behind it is an adult version of the same jacket displayed with several sewer elbow pipes. Apparently, the pipes inspired the shape of the sleeve, a good example of the unconventional way James visualized in three dimensions. The center vitrine displays another James’ innovation—the down-filled jacket, a design so advanced it wouldn’t re-appear again until the 1980s.

You can also get a glimpse of James’ waspish personality from a typewritten list he wrote in the 1960s where he ranked the rest of the fashion world with statements like: “Photographers who I felt unable to catch the essence of fashion—Horst and Avedon.” Even more cutting was his assessment of Erte. “Illustrative of designer artists whom I abhorred and thought their pretension to represent fashion disgraced it.” Ouch.

Next to the archive room are the garments James felt were some of his best—tailored coats with seams that curve and shape the body yet allow a “breeze of air to linger between body and fabric.” Made of firm wools like melton, flannel, and cavalry twill, James’ coats look like they could stand-alone. He seems to have learned from his mistake, made around 1936—the bias-cut coat in loosely woven plaid featured in the recent exhibit at The Museum at FIT. That coat stretched out of shape since James was still learning the how to handle bias draping. The coats on display show James’ millinery training at work in the curved collars and molded bust lines that fit the body without the use of darts.

Also on view in this room are a number of cocktail dresses, suits, and evening gowns, including the Diamond Dress (1957), the Sirène (1951-52), and the Taxi Dress (c. 1932). Video animation gives a valuable insight into the way his clothing was constructed.

This would be enough for most exhibits, but mounted in the Special Exhibitions gallery in the south wing are the gowns James is famous for—15 ball gowns whose construction amazes the fashion world today. Each is mounted on its own platform, which allows viewing from all sides. Instead of label cards, each has an animated screen attached to a robotic camera. As the camera roams over the dress, the screen highlights crucial details. Pattern pieces float apart so one can see the shape and then are applied to a form so we can understand how they fit together. To get the unconventional shapes he wanted, James used unconventional materials like nylon mesh, millinery willow, polyester horsehair braid, and blocking net–materials used by milliners. He also used Pellon, a nonwoven interfacing that contains nylon and synthetic rubber among other materials to expand the shape of many of his garments, like the famous Clover Dress (1953). This was the 1950s when “wonder fibers” were advertised in Vogue. James bent them all to his vision.

James would have liked all this analysis. He wanted the public to learn from his work. He made up muslins of his dresses especially for a 1948 exhibit at the Brooklyn Museum. These are now visible in a separate room at the entrance of the second gallery. In their midst sits the Butterfly Sofa (1950), made for the de Menil family home in Houston, an early example of ergonomic design and a mark of James’ only attempt at interior design. Next to this room is a 1949 portrait of his client, Millicent Rogers, resplendent in a James gown. Rogers looks out at us with a haughty, bemused smile as if she knows none of the women who appeared at this year’s Met Gala will ever outshine shining society swans who were dressed by Charles James.

After looking at this exhibit one can conclude that designers can learn from James, but his world will never come again. Those days of couture splendor I dreamt about many years ago were ending even then. What remains is his body of work that illustrates his belief that “A good design should be like a well-made sentence, and it should only express one idea at a time.” James’ design principles still inspire. They can still make us dream. It’s worth visiting this exhibit several times to absorb them.

Additionally, it provides an admittedly incomplete inventory of fashion exhibitions since 1971. While Lou Taylor’s book, Establishing Dress History does much to document fashion collections and their history in text, Clark and de la Hayes’ book not only discusses the history of exhibitions of fashion, but does so in an oversized, illustrated volume (including photos of historic exhibition catalogs, as well as installation photos).

Additionally, it provides an admittedly incomplete inventory of fashion exhibitions since 1971. While Lou Taylor’s book, Establishing Dress History does much to document fashion collections and their history in text, Clark and de la Hayes’ book not only discusses the history of exhibitions of fashion, but does so in an oversized, illustrated volume (including photos of historic exhibition catalogs, as well as installation photos).