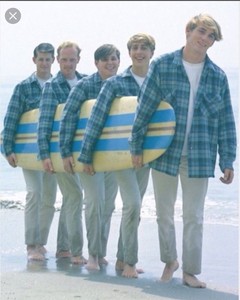

Popular in the Fall and Winter, wool plaid flannel shirts have long been associated with the rugged outdoors of the Pacific Northwest, and in the 1990s came to represent the Grunge music scene that originated in that area. Developed by Pendleton Wollen Mills (in Oregon) in the 1920s, colorful flannel shirts started out represent blue-collar work such as logging, along with outdoor recreation such as hunting and fishing.

The Beach Boys, (whose original name had been “The Pendletones”) helped to popularize the Pendelton flannel more widely, especially the Umatilla wool shirt, among California surfers in the 1960s (Pendleton 2019).

The shirt took on new meaning during the 1990s when Grunge music, and vintage, retro, and thrift-store fashions took center stage, thanks in large part to bands like Nirvana, Pearl Jam, and Hole. The style was especially popular with members of Generation X, who were young adults and teenagers at the time.

With the 1991 release of Nirvana’s “Smells Like Teen Spirit” and Pearl Jam’s “Ten” album, Grunge (and the requisite flannel shirts) hit the mainstream. Grunge music, Gen Xers, and the flannel shirt took center stage in popular films such as Singles (1992), directed by Cameron Crowe and Reality Bites (1994) directed by Ben Stiller. The films depicted Gen-Xers and band members of Pearl Jam, Soundgarden, and Mudhoney wearing flannel in the Pacific Northwest.

Costume Design by Jane Ruhm .

Fashion designers such as Marc Jacobs (b. 1963), Calvin Klein (b. 1942), and Anna Sui (b. 1964) picked up on the trend and incorporated grunge into their collections in the early 1990s. Grunge style one of the prime examples of the workings of the bottom-up fashion trends of the late-twentieth-century whereby street styles were adopted by designers and clothing manufacturers and then copied massively by the mainstream market.

Among the most newsworthy grunge collection was the Spring 1993 Perry Ellis collection designed by Marc Jacobs. The collection earned Jacobs the nickname “guru of grunge.” He even sent a sample of the collection to Kurt Cobain (of Nirvana) and Courtney Love (of Hole). Love has said, “Do you know what we did with it? . . . We burned it..” (Madsen 2013)

By the late 1990s, the grunge era of music had ended, though Grunge-inspired styles returned to runways and streetwear several times during the two decades following the early 1990s. Ironically, twenty-five years later, Grunge fashions have returned as a new ‘retro’ fashion. Marc Jacobs reissued his original 1993 Grunge Collection in November of 2018, complete with a Dr. Martins boots collaboration (Yotka 2018).

This post is one in a series that gives readers a sneak-peek into my new book Artifacts from American Fashion (Available November 30), as well as the research behind it. The book offers readers a unique look at daily life in twentieth-century America through the lens of fashion and clothing. It covers forty-five essential articles of fashion or accessories, chosen to illuminate significant areas of twentieth-century American daily life and history, including Politics, World Events, and War; Transportation and Technology; Home and Work Life; Art and Entertainment; Health, Sport, and Leisure; and Alternative Cultures, Youth, Ethnic, Queer, and Counter Culture. Through these artifacts, readers can follow the major events, social movements, cultural shifts, and technological developments that shaped our daily life in the U.S.

Heather Vaughan Lee is the founding author of Fashion Historia. She is an author and historian, whose work focuses on the study of dress in the late 19th through the 20th century. Covering a range of topics and perspectives in dress history, she is primarily known for her research on designer Natacha Rambova, American fashion history, and the history of knitting in America and the UK. Her forthcoming book, Artifacts from American Fashion is available for pre-order on Amazon (November 2019 from ABC-CLIO). More posts by the Author »

Sources:

Madsen, Susanne. 2013. “The story of Marc Jacobs’ controversial 90s grunge

collection.” Dazed & Confused. August. Accessed August 19, 2019.

https://www.dazeddigital.com/fashion/article/16706/1/marc-jacobs-for-perry-ellis.

Yotka, Steff. 2018. “Marc Jacob’s Grunge Collection for Perry Ellis Is Back! See Every Look.” Vogue. November 7. Accessed January 7, 2018. https://www.vogue.com/article/marc-jacobs-perry-ellis-grunge-collection-reissue-lookbook.