“Punk:Chaos to Couture” A crowd-sourced review

During my very busy trip to New York last week, I was able to squeeze in visits to two fashion exhibitions. FIT’s RetroSpective (briefly reviewed here), and the Met’s Punk: Chaos to Couture.

Much has already been said about the Met’s show – what it has, and what it doesn’t have, what it should be, and what it is not. But many of those reviewers were allowed access to the show in a special media-only preview, without the ‘common man/woman’ present. One of my favorite parts of seeing a fashion exhibition is hearing the reactions of lay-people to shocking designs. Punk: Chaos to Couture, is nothing if not a showcase of extreme styles.

The introductory text reminds viewers of the key elements of punk that have been adopted by couturiers, notably the “sexual and political energy” and the “do it yourself legacy.” Curator Andrew Bolton also acknowledges that “the ethos of punk is at odds with couture” and that “punk caused a breaking of barriers between production and consumption.” This introductory text was read by only a handful of people while I was there – a Wednesday early afternoon. The exhibition drew people from many different walks of life: young, old, men, women, New Yorkers and visitors. It wasn’t overly packed, but it wasn’t empty either.

As I came upon the first major ‘wow’ of the show, the recreation of the infamous CBGBs bathroom (with toilet seats up and cigarettes on the floor), two twenty or thirty-something blonde girls snarked, “Really?” and wandered off towards the first gallery of couture. Sure, at first glance, one might not immediately see the connection to fashion. But later rooms reveal that the distressed, deconstructed, graffiti-ed bathroom is easily referenced in the organization of the show – and seems to provide the guiding outline for the rest of the show.

As I walked past the requisite Westwood t-shirts (the 1%ers), saw the quote from journalist Caroline Coon that called Malcolm McLaren the Diaghilev of punk, and the recreation of the Seditionaires shop, I came to the Rodarte knitwear in the “Clothes for Heroes section. I am a sucker for couture knit and crochet, and this 2008 red and black dress over tights (in synthetic, itchy-looking yarn), caught my eye. An adult woman supervising some pre-teens said to her charges, “I could see you in something like that” – perhaps as a way to engage them. But I wondered about the seemingly innocuous comment.

I was engrossed in the DIY hardware section – Zandra Rhodes, Versace, and Givenchy, with the always-clever Moschino (but secretly I wondered where the Donna Karan hardware dresses were). Focused on my own thoughts in this long hall, I didn’t overhear much (especially given the loud disruptive beeping that was surprisingly audible over the equally loud music and video-loops).

I immediately liked the D.I.Y. Bricolage featured in the next room, with the softer textured pink walls, and equally softened clothes. As I was noticing the differences from the last room, I heard an older man say “I like this room, I like this lighting.” I noticed others nodding and relaxing here – though the clothes had volume, there was less volume in the music, videos, and lighting – as the gentleman pointed out. In particular, I liked the fluffy Pugh trash bag dresses (2013-2014), and the Margiela jackets. As I noticed the Moschino plastic shopping bag dress, I wondered if that might be a historic piece now that plastic shopping bags were being banned in California (and perhaps elsewhere soon). I crushed hard on the McQueen Bubble-wrap dress (2009-2010) as I left the room.

The graffiti room held more famous McQueen’s, and beautiful painted Dolce and Gabbana ball-gowns (2008) but I was intrigued by the Belgian designer Ann Demeulemeester. As I was checking those out, an older woman in a wheelchair said “these are fantastic” and had her assistant push her closer so that she could see more detail in the dark room with dark walls.

The next room (D.I.Y. Destroy) somehow reminded of the Vivienne Westwood show at the V & A, and of the Gaultier show at the de Young. As I walked down the lines of static mannequins, I came upon what turned out to be the signature piece of the show.

Some young girls guffawed out loud at the sight of the distressed Chanel suit from 2011. I had mixed feelings that I couldn’t nail down. I could see the humor and irony of finely-made couture being torn to shreds, but there was also something very wrong about such fine craftsmanship being distressed to meet a passing trend. It seemed desperate and didn’t match the well-established Chanel tradition.

Ultimately, that might be my feelings about the whole show – clever, but trying too hard. I don’t know – I’m still sorting it out. Interestingly, the people whose comments I heard were all positive – I like this, that’s beautiful, I could see wearing this. What I don’t know is what those people thought of the show overall. Did you see the show? What did you think?

Fashion Exhibitions in NYC: RetroSpective at FIT

My trip to NYC this week is jam-packed with book related things, but I did manage to take in the RetroSpective exhibition currently on view at the Museum at FIT (May 22-November 16, 2013).

Curated by Jennifer Farley, with textiles organized by Lynn Weidner and accessories by Colleen Hill, RetroSpecitve is my favorite kind of fashion exhibition: It’s focus is on historical representations of fashion throughout history. Though small, it is well-informed and carefully selected to show how the history of fashion is a constant source of inspiration for designers, and has been for hundreds of years. This is not something new, as some would suggest. This small but significant exhibit covers 250 years of revivalism, “from the 18th century to grunge.”

The culture of revival is presented here with beautiful examples from FIT’s collection of couture: ensembles, under-structures, dress-forms, textiles, and accessories. It is supported by two video’s from British Pathe, highlighting revivals of the 1920s style in the 1950s, and also of monastic dress in the 1940s.

After an introductory image depicting the changing silhouette of fashions by Ruben Toledo, the exhibition is grouped by style or trend, and includes sections on hoops, bustles, panniers, and 1830s style puffed sleeves, pin-stripes, and more. One of my favorite aspects of this show, was the connections draw between designers of different time periods. Cat Chow juxtaposed with Claire McCardell, Paco Rabanne paired with Yohji Yamamoto, a beautiful 1951 Balmain evening gown is paired with an 18th century robe a la Anglaise, and so on. Some of my favorites surprised me (as I don’t typically go for anything post 1980): a beautiful 1980 YSL evening gown of changeable purple taffeta with puffed sleeves (a la 1830s), a 1996 Yoshiki Hishinuma hooped gown (mixing eastern and western cultures, picture above), and not surprisingly, an Elsa Schiaparelli bustle gown from the 1930s (seen at right). Shoes, handbags, undergarments, upholstery, and other textile designs round out the exhibit and make for a rich experience.

If you happen to be in New York anytime soon, it’s well worth a visit.

P.S.: Did you know that there was a Fashion Archive at the British Pathe Website?

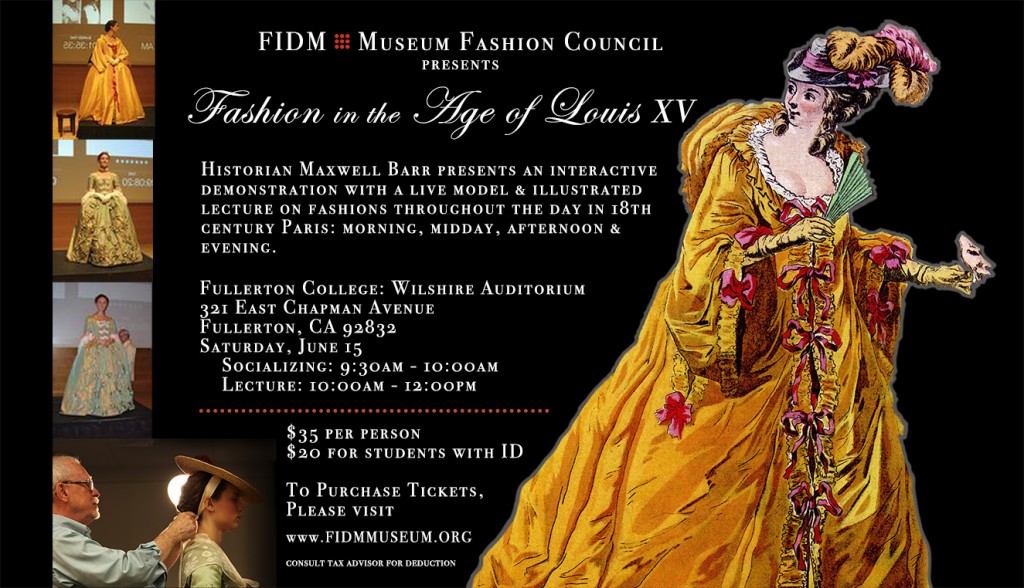

Go behind the scenes at Pageant of the Masters with CSA Western Region

The Costume Society of America, Western region is adding a bonus event for 2013 (and this is your one place to find out about it!) The Pageant of the Masters in Laguna Beach is “ninety minutes of ‘living pictures’ – incredibly faithful art re-creations of classical and contemporary works with real people posing to look exactly like their counterparts in the original pieces.”

Celebrating it’s 80th anniversary, Diane Challis Davy, director of the Pageant of the Masters, notes “We’ll have Vermeer, Gainsborough, Michelangelo, Gerome, Seurat, Rodin, Norman Rockwell. Designers for both stage and screen look to paintings and sculpture for historical information and inspiration. I thought it would be a new twist for the Pageant to take a look back at the work of the Masters that inspired great works of cinema.” And, of course, the show will once again conclude with its traditional finale, Leonardo da Vinci’s “The Last Supper.”

To be held on August 18, those who register for the CSA program will be treated to:

- a talk by Pageant Costume and Headpiece Director and CSA Member, Mary LaVenture

- a performance of The Big Picture (a salute to classic art that inspired legendary filmmakers)

- a post-performance backstage tour

Below are some photos from past years of the show to entice you:

Looking ahead to Fall Books on #FashionHistory

In the world of publishing, it is a very busy time (hence my lack of posting anything for the last month). Publishing houses are busily confirming books to be released for the fall season, and to be presented to booksellers (and media) at Book Expo America at the end of May in New York (coincidentally and always timed for the same time as the Costume Society of America’s National Symposium).

So – I’ve been trolling the virtual shelves of new material to see what we’ll have in September and thought I’d share a ‘sneak peak’ of what is to come. With any luck, I’ll be reviewing a few of these in more depth once the books are out!

An illustrated monograph of haute couture designer Jean Patou’s life and career during the apex of twentieth-century glamour, drawn from previously unpublished family archives. An illustrated monograph of haute couture designer Jean Patou’s life and career during the apex of twentieth-century glamour, drawn from previously unpublished family archives. During the 1920s and 1930s, the French couturier Jean Patou was Chanel’s main rival: day pajamas, jersey sportswear, swimwear, and the little black dress were all among the innovative designs marking Patou’s remarkable, albeit brief, career as the king of Parisian fashion. With his untimely death at 49, he had only fifteen years to make his mark on the history of couture, yet in that short time he amassed a colossal fortune, opened shops and studios in Paris, Deauville, Biarritz, and New York, and invented some of the world’s legendary fragrances, including Joy and Que Sais-Je. This book recounts the story of Patou’s charmed life and career during the most glamorous years of the twentieth century. For the first time, the heirs of the Patou family have agreed to share their extensive private archives, and author Emmanuelle Polle spent more than two years reviewing thousands of unpublished documents: photographs, diaries, client lists, and original, hand-colored sketches. Signed by major names in fashion photography (Baron de Meyer, Laure Albin Guillot, or the Seeberger brothers), the vintage photographs-presented alongside fashion designs, original fabric swatches, art deco furniture, perfume bottles, and garments photographed especially for this volume-retrace the universe of this extraordinary aesthete and speak of a certain minimalism. This book is an essential reference for anyone interested in the history of fashion and of the greatest years of Parisian style.”

Of course there is lots of talk about “Gatsby” now, and the book trade can sometimes be slow to respond. Fashion in the time of the Great Gatsby will be out on September 24, 2013 by LaLonnie Lehman, a professor of Theatre at Texas Christian University at Fort Worth ( she is a member of the United States Institute for Technical Theatre and the Costume Society of America). The book’s official description reads:

The post-WWI world saw cultural, political and technology explosions that lead the way to fashion becoming a highly personal and social statement. The Roaring ’20s, exemplified by F. Scott Fitzgerald’s literary classic The Great Gatsby, ushered in a new era of liberation in dress for style, comfort, movement, expression, and attraction. This book chronicles the story of this milestone era in fashion history and spans the entire wardrobe for men and women, including day and evening wear, accessories and brand new categories such as “casual clothes” and “fads” like smoking jackets, tiaras, and cigarette holders. Written by a noted academic in fashion history and a costume designer herself, it is beautifully illustrated with period photographs and fashion sketches that are highly evocative of the period and the stylish world of The Great Gatsby.”

- Vintage Fashion Illustration: From Harper’s Bazaar 1930 – 1970 (September 3, 2013)

- Lee Miller in Fashion (September 9, 2013)

- Dior Impressions: The Inspiration and Influence of Impressionism at the House of Dior (September 17, 2013)

- An American Style: Global Sources for New York Textile and Fashion Design, 1915-1927 (September 28, 2013)

More to come on these and other titles as they are released!

Southeastern European Folk Dress: A CSA Event with Dr. Elizabeth Barber

Earlier this month I had the rare pleasure of taking a Costume Society of America (CSA) Western Region tour of Resplendent Dress from Southeastern Europe: A History in Layers, the current exhibition on at UCLA’s Fowler Museum, with one of the world’s foremost historians on the earliest known clothing. Dr. Elizabeth Barber is an expert in archaeology and textiles who has been become well known for her research on 20,000-year-old clothing, archaeological finds, and historical connections, since earning her PhD from Yale in 1968.

Only twenty CSA Western Region members and guests would fit on this exclusive tour, and it was a pleasure not to be missed! We not only learned a tremendous amount about the early history of clothing in Southeastern Europe (everything from Albania to Croatia to Romania and all points in between) – but we learned how the forms and symbols connected through history.

The exhibition, tour and talk were not only informative but also beautiful. The garments on display were the best of the Fowler’s collection of folk wear from the 20th century, beautifully dressed, displayed, and organized. The detail in the handwork in each and every piece was breathtaking, awe-inspiring, and taken in all at once is mind-boggling. I could have stared at each piece for a lot longer just to look at the details. One of the best parts of the exhibition is the attention to detail: Many of the mannequins have complete ensemle -d own to the shoes and socks and up to the headdress.

The exhibition, tour and talk were not only informative but also beautiful. The garments on display were the best of the Fowler’s collection of folk wear from the 20th century, beautifully dressed, displayed, and organized. The detail in the handwork in each and every piece was breathtaking, awe-inspiring, and taken in all at once is mind-boggling. I could have stared at each piece for a lot longer just to look at the details. One of the best parts of the exhibition is the attention to detail: Many of the mannequins have complete ensemle -d own to the shoes and socks and up to the headdress.

The exhibition is up through July 14th and is breathtaking. For more on the CSA Western Region tour of the exhibition, watch for the September issue of the CSA Western Region newsletter. To be the first to know about upcoming events and tours through CSA Western Region, Join here.

Dr. Barber has also produced a wonderful book documenting her research and the exhibition (I bought my copy on the spot): Resplendent Dress from Southeastern Europe.

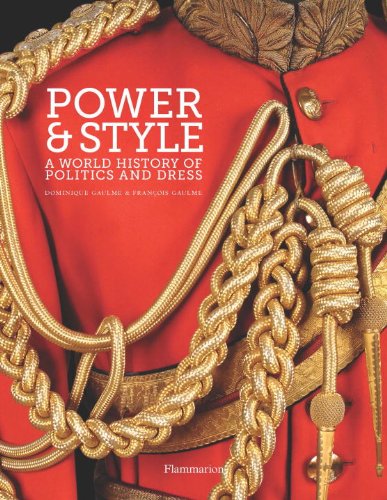

Power & Style: A World History of Politics and Dress (Guest Book Review)

Today, I’m pleased to bring a book review of review of Power & Style: A World History of Politics and Dress By Dominique Gaulme and Francois Gaulme (Translated from the French by Deke Dusinberre) from a dear friend. José Blanco F. is an Associate Professor in the Textiles, Merchandising and Interiors Department at the College of Family and Consumer Sciences and manager of the college’s Historic Clothing and Textile Collection. He is originally from Costa Rica and has a Ph.D. in Theater from Florida State University. His current research focuses on dress and popular culture in the second half of the twentieth century with an emphasis on male fashion. He is also interested in the fashion and visual culture in Latin America and the application of Jungian archetypal analysis to fashion. José is the Vice-president of Education for the Costume Society of America.

Today, I’m pleased to bring a book review of review of Power & Style: A World History of Politics and Dress By Dominique Gaulme and Francois Gaulme (Translated from the French by Deke Dusinberre) from a dear friend. José Blanco F. is an Associate Professor in the Textiles, Merchandising and Interiors Department at the College of Family and Consumer Sciences and manager of the college’s Historic Clothing and Textile Collection. He is originally from Costa Rica and has a Ph.D. in Theater from Florida State University. His current research focuses on dress and popular culture in the second half of the twentieth century with an emphasis on male fashion. He is also interested in the fashion and visual culture in Latin America and the application of Jungian archetypal analysis to fashion. José is the Vice-president of Education for the Costume Society of America.

Here is his review:

Power & Style: A World History of Politics and Dress is a new book written by French journalist Dominique Gaulme and anthropologist and historian Francois Gaulme. It was translated from the French by Deke Dusinberre. This volume adds to the expanding literature discussing the history of dress and fashion from a global perspective. The authors emphasizes the role of dress as a symbol of power through history and discusses a variety of settings from tribal communities to monarchs and elected officials.

The work is organized chronologically in an easy-to-follow format with a vast number of illustrations for support. There are two main problematic issues with the authors’ approach. First, the authors almost exclusively discuss political power concentrating on individuals declared powerful by either a political system (Kennedy, Reagan) or themselves (Napoleon, Hitler).

The book, thus, equates power exclusively with politics and government institutions and ignores other power systems; not discussing, for instance, the impact of corporate power dressing and personal appearance management as well as the power achieved by celebrities in a variety of fields and how they exert a powerful influence through their wardrobe. Second, and more important, is the authors’ decision to include very little discussion on influential women and justifying the decision by stating that “… women’s access to legitimate political power is very recent.” Therefore the book virtually ignores women who have been powerful monarchs and rulers mostly casting aside an extensive list ranging from Cleopatra, Elizabeth I, and Queen Victoria to Golda Meyer and Indira Ghandi. These women, along with many others, held political power as appointed or elected rulers and cleverly used their appearance and dress to express and symbolize their authority. For instance, the authors choose to discuss the “Victorian” era by analyzing Prince Albert’s wardrobe in detail and just briefly mention Queen Victoria thus assuming that sartorial power at that time was mostly expressed through male dress.

So, the book would be better titled and promoted as what it really is: a history of men’s fashion told from the perspective of the connection between power, style, and dress. Once the reader accepts that limitation, then the work becomes an enjoyable read. The authors lay out a good case for the argument that dress plays functions that go beyond mere protection of the body and that decoration and indication of status are primary functions.

The authors develop connecting threads with pertinent examples in each chapter, easily capturing the attention of anyone new to dress history but they also provide a purposeful synthesis of the topic and a variety of relevant details for experts and students in the field.The book is lavishly illustrated in full color and often full page images in high quality reproduction that sometimes jump from the page almost as an actual canvas. There are numerous portraits of subjects discussed in the book, but in almost every instance the illustrations should be more directly related to and referred in the text with more specific descriptions of dress and sartorial symbols in the portraits selected to illustrate the chapters.

The historical research is thorough; the book is well organized and narrated in an appealing manner with elegant descriptive language that easily transports the reader to the places and periods described. The chronological approach cleverly and effectively carries the reader from what the authors call “naked societies” where the right to wear certain objects such as feathers was a symbol of power to ancient Rome and Byzantium. The authors, for instance, paint a clear image of Augustus in Imperial Rome, calculating the precise fullness of his toga as a way to manage the full transition of Rome from Republic to Empire, or Hitler rummaging in his mind about ways in which his adoption of modest forms of dress could distinguish him from the spectacular uniforms formerly used in Germany. It is then in the storytelling and sharing of anecdotes and factoids that the book is stronger.

Powerful male figures through history are highlighted as examples, including Constantine, Philip the Good, Louis XIV of France, and Charles II of England. Famous dandy Beau Brummell is one of the few men discussed in the book whose sartorial power did not arise solely from political power but from social power as Brummell promoted the idea of dressing as a moral exercise in simplicity and elegance.

Andrea Appiani the elder, Napoleon I, King of Italy, 19th Century, Oil on Canvas, Napoleonic Museum, Ille d’Aix. Other notable figures discussed include Napoleon, Prince Albert, and Edward VII, who is portrayed as a man so passionate about clothing that he was often considered vain and wasteful. The book argues that Edward VII had a remarkable impact on the development of cosmopolitan wardrobe to accommodate twentieth century active lifestyles. Once the book reaches the twentieth century, however, it rushes in one chapter from Hitler to Mao emphasizing how totalitarian regimes and their leaders used dress as a symbol of power.

American style is discussed in one chapter, with John F. Kennedy marked as a leading figure in the casualization of the American look and the development of the country’s obsession with comfort and muscularity. Most of the book emphasizes European and American trends and although one of the last chapters is titled: “The UN: Going Global” it still discusses current trends in men’s dress by analyzing two opposing schools of masculine elegance in the closing decades of the twentieth century: the English tradition with structured pieces and an air of formality, and the Italian tradition with lighter fabrics and cuts emphasizing the male body. The chapter also discusses the transition at the United Nations from representatives attending in their countries’ traditional or representative attire to a general acceptance of business attire.

The book closes with two chapters discussing current and future trends. The authors revert to the idea that women did not occupy positions of power until the twentieth century and expect the reader to be surprised upon receiving this information. Still, with a long list of powerful women in the twentieth century, the book devotes just mere sentences to some of them (Margaret Thatcher, Hillary Clinton, Benazir Bhutto, Angela Merckel) and ignores other powerful females such as Eva Perón and a long cast of female heads of state in Latin America and other areas of the world. The final chapter aims to predict how the relation between power and dressing will evolve in the future. The authors also include smaller sections at the end of each chapter discussing different elements of clothing and the function they have played throughout history in determining power and status for men. These sub-chapters include a wide range of objects such as the penis sheath, crowns, swords, cravats and neckties, top hats, whiskers, scepters, boutonnieres, and watches.

Overall the book is an enjoyable read and, as stated above, the illustrations are multiple and of high quality. It adds to the growing literature on men’s fashion and style. Perhaps to solve the issue of ignoring powerful women; the authors should compose a second volume addressing how women have used dress and style as a symbol and instrument of power through the ages.”

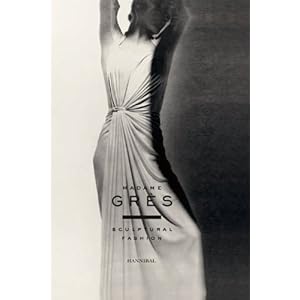

Madame Grès: Sculptural Fashion (Book Review)

The book Madame Grès: Sculptural Fashion commemorates the ever-ephemeral fashion exhibition of the same name (which closed at MoMu Fashion Museum, Province of Antwerp in February of this year) and adds to the growing body of knowledge on this important twentieth-century designer.

The book Madame Grès: Sculptural Fashion commemorates the ever-ephemeral fashion exhibition of the same name (which closed at MoMu Fashion Museum, Province of Antwerp in February of this year) and adds to the growing body of knowledge on this important twentieth-century designer.

Often re-interpreting classical Greek sculptural forms, and best known for her classical draping and pleating, Madame Alix Grès (1903-1993) was inspired by the body and was fiercely dedicated to her work. Though active from the early 1930s (as Alix Barton), her career as Madame Grès began when she opened a couture house under that name in 1942. Her clients included the likes of the Duchess of Windsor, Marlene Dietrich, Greta Garbo, Jacqueline Kennedy, and Dolores del Río.

With this volume, Olivier Saillard, director of Galliera, The Paris Museum of Fashion, adds his name to the prestigious list of fashion historians who have documented the work of Grès. Previous books have been penned by such fashion history giants as Richard Martin and Harold Koda of the Metropolitan Museum of Art (Madame Grès 1994) and Patricia Mears of the Fashion Institute of Technology (Madame Grès: the Sphinx of Fashion, 2007).

Madame Grès: Sculptural Fashion is a wonderful resource for historians already familiar with her history and who are looking to add further to their libraries. It documents the garment and sketch collections held at the Galliera, while offering the best of the details of her career including: insights into her public persona, her relationship with the media, her opinions on exhibitions of her work planned during her lifetime (they weren’t positive), her design process and philosophy, and much more.

The 216-page-book is full of photographic evidence of her work, as well as some photos of work she inspired other modern designers to create (Jean Paul Gaultier and Yogi Yamamoto among them). The “Couture Studio” section of the book presents photographs of some sixty extant garments created between 1933-1988 (with captions at the back of the book), followed by a section of contemporary high fashion photographs of Grès work. A selection of the 2,800 sketches/illustrations donated by the Pierre Bergere – Yves Saint Laurent Foundation leaves you wanting more and a section called “Biography” presents a sort-of annotated narrative chronology interspersed with illustrative images. Despite all of the material included, I found the book’s small trim size and layout too be somewhat awkward –many images occupied only the top half of a page in a smallish size, making many design details difficult to see. This left the bottom third of the page more-or-less blank, yet captions were at the back of the book. This design made little sense to me.

Despite these few shortcomings, I’d recommend this book for the true fashion historian, museum fashion curator, libraries with strong fashion sections, and the devoted enthusiast.

Look inside the book:

I’m in Knitting Traditions Magazine !

Due to hit shelves on April 9, the next issue of Knitting Traditions not only includes 25 historical knitting patterns (including an article about Knitting and the Brontë sisters), but also has two extra treat: an article I wrote on the 40-year history of Jack Frost Yarn and a pattern I derived from a booklet the company put out in 1953.

My article, The Jack Frost Yarn Company and the History of  Handknitting in the United States was a joy to research and write, has some nice historical photos, with a good dose of fashion history to boot. The little vintage basket-weave baby sweater, in butter yellow, knit-up quickly and was easy to do. The pre-order page for Knitting Traditions Spring 2013 issue notes:

Handknitting in the United States was a joy to research and write, has some nice historical photos, with a good dose of fashion history to boot. The little vintage basket-weave baby sweater, in butter yellow, knit-up quickly and was easy to do. The pre-order page for Knitting Traditions Spring 2013 issue notes:

Learn about the history of the Jack Frost Yarn Company and its popular, now-vintage knitted pattern books, as written by Heather A. Vaughan. Enjoy photographs of early Jack Frost pattern booklets and create your own vintage baby cardigan with the Jack Frost Baby Cardigan knitting pattern.”

I can’t wait to get my copy in hand, and see people start to actually knit up the cardigan! All the more reason to look forward to springtime.

New Resources on Early Hollywood (Book Round-Up)

Over the past few months some books have landed on my desk all surrounding the same topic: dress and appearance in early Hollywood. Here’s a quick round-up of these newly available resources (all still on my ‘to read’ list):

Go West, Young Women!: The Rise of Early Hollywood (January 2013, UC Press)

By Hilary Hallett

In the early part of the twentieth century, migrants made their way from rural homes to cities in record numbers and many traveled west. Los Angeles became a destination. Women flocked to the growing town to join the film industry as workers and spectators, creating a “New Woman.” Their efforts transformed filmmaking from a marginal business to a cosmopolitan, glamorous, and bohemian one. By 1920, Los Angeles had become the only western city where women outnumbered men. In Go West, Young Women! Hilary A. Hallett explores these relatively unknown new western women and their role in the development of Los Angeles and the nascent film industry. From Mary Pickford’s rise to become perhaps the most powerful woman of her age, to the racist moral panics of the post-World War I years that culminated in Hollywood’s first sex scandal, Hallett describes how the path through early Hollywood presaged the struggles over modern gender roles that animated the century to come.”

Precocious Charms: Stars Performing Girlhood in Classical Hollywood Cinema (January 2013, UC Press)

By Gaylyn Studlar

In Precocious Charms, Gaylyn Studlar examines how Hollywood presented female stars as young girls or girls on the verge of becoming women. Child stars are part of this study but so too are adult actresses who created motion picture masquerades of youthfulness. Studlar details how Mary Pickford, Shirley Temple, Deanna Durbin, Elizabeth Taylor, Jennifer Jones, and Audrey Hepburn performed girlhood in their films. She charts the multifaceted processes that linked their juvenated star personas to a wide variety of cultural influences, ranging from Victorian sentimental art to New Look fashion, from nineteenth-century children’s literature to post-World War II sexology, and from grand opera to 1930s radio comedy. By moving beyond the general category of “woman,” Precocious Charms leads to a new understanding of the complex pleasures Hollywood created for its audience during the half century when film stars were a major influence on America’s cultural imagination.”

Hollywood Before Glamour: Fashion in American Silent Film

(January 2013, Palgrave)

By Michelle Finamore

This exploration of fashion in American silent film offers fresh perspectives on the era preceding the studio system, and the evolution of Hollywood’s distinctive brand of glamour. By the 1910s, the moving image was an integral part of everyday life and communicated fascinating, but as yet un-investigated, ideas and ideals about fashionable dress.”